Shahed: The Story of the "Martyr" Drone

Iran’s military strategy was born out of necessity. A country heavily sanctioned by the West, intended to cripple it, accidentally made it a formidable opponent in drone warfare. Without the production of important materials needed for aircraft, the Islamic Republic of Iran turned to cheap drones that evolved into highly technological advancements, capable of performing million-dollar results at thousand-dollar costs. One branch of Iran’s drone program is the Shahed. Shahed translates into “Martyr” or “Witness,” and these drones are designed for combat. It is a reflection of the mindset behind the platform. These drones are intended to sacrifice themselves. These low-cost and highly adaptable drones are now beginning to shape the battlefield in Ukraine. These Shaheds are a combination of mass production, expendability, and intent that allows Iran to bypass sanctions and project its influence on the world. Today, the Shahed 131 and 136 are symbols of loitering munitions; they have wreaked havoc all over Ukraine and the Middle East. Understanding the Shahed platforms can give a glimpse into the future of warfare.

Iran’s first experiment with drones happened during the Iraq–Iran War. These unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) were introduced at a time when Iran was losing aircraft faster than it could replace them. Western sanctions cut off access to key critical parts for aircraft such as the F-4s and F-5s. However, UAVs offered a practical alternative to the Iranians. Early drones like the Mohajer-1 provided critical information on enemy troop emplacements without the risk of losing pilots or aircraft.

By the late 1990s to early 2000s, Iran was transitioning from surveillance drones to more sophisticated platforms. The Shahed drone family is an extension of this sophistication. Shahed literally means martyr or witness. It was a representation of a design philosophy rooted in destruction and chaos. The concept was fairly simple: create drones that would inflict massive damage while offering no risk of loss to personnel or equipment.

The beginnings of the Shahed were found in the Shahed-123. While Iran never officially confirmed its designation, open-source evidence strongly supports its existence. In February 2014, a small drone crashed in Saravan, Iran. Photos revealed a compact drone with a V-tail, lightweight construction, and a piston engine. In May 2015, Turkish forces shot down a drone along the Syrian–Turkey border, and the wreckage closely resembled the drone in the 2014 crash. Both wreckages revealed the same characteristics: V-tail, engine placement, and simple landing feet. Bellingcat traced similar sightings in Syria, including a drone wreckage in southern Aleppo. All signs indicated that Iran might have tested early versions of the 123 in active conflict zones. While these early cases resulted in crashes, the goal was to gain data. Syria was the perfect testing ground due to multiple proxies and militia groups fighting among themselves.

In the mid-2000s, Shahed Aviation Industries, in conjunction with HESA, developed a more complex Shahed: the Shahed-129. This was the first attempt at a Medium-Altitude, Long-Endurance platform. This drone eerily resembles the American MQ-1 Predator.

In early 2012, the Shahed-129 flew, with additional prototypes following soon after. This was revealed in a public exercise in September 2012 during the “Great Prophet 7” war games. Iran claimed that this drone could fly for 24 hours and carry guided munitions. Production of the Shahed-129 did not begin until 2013. While the model was initially intended for surveillance, it wasn’t until 2016 that this drone was equipped with Sadid-345 precision munitions, capable of precise airstrikes. What is shocking is that this drone, in comparison to the MQ-1 Reaper, was significantly cheaper. Iranian drone philosophy evolved around inexpensive material and drones designed to deliver million-dollar results. By the mid-2010s, Iranian engineers harnessed the benefits from early drone testing to develop two guided-munition drones: the Shahed-131 and the Shahed-136. These triangular-shaped drones would begin to dominate the battlefield and eventually make their way to Ukraine as the Geran-2.

By the mid-2010s, the Shahed family evolved from providing reconnaissance to becoming a new generation of lethal, low-cost, mass-deployable systems. These variants, the Shahed-131 and Shahed-136, were now developed with only one mission in mind. From observation to destruction, these Shaheds were designed to directly target the enemy.

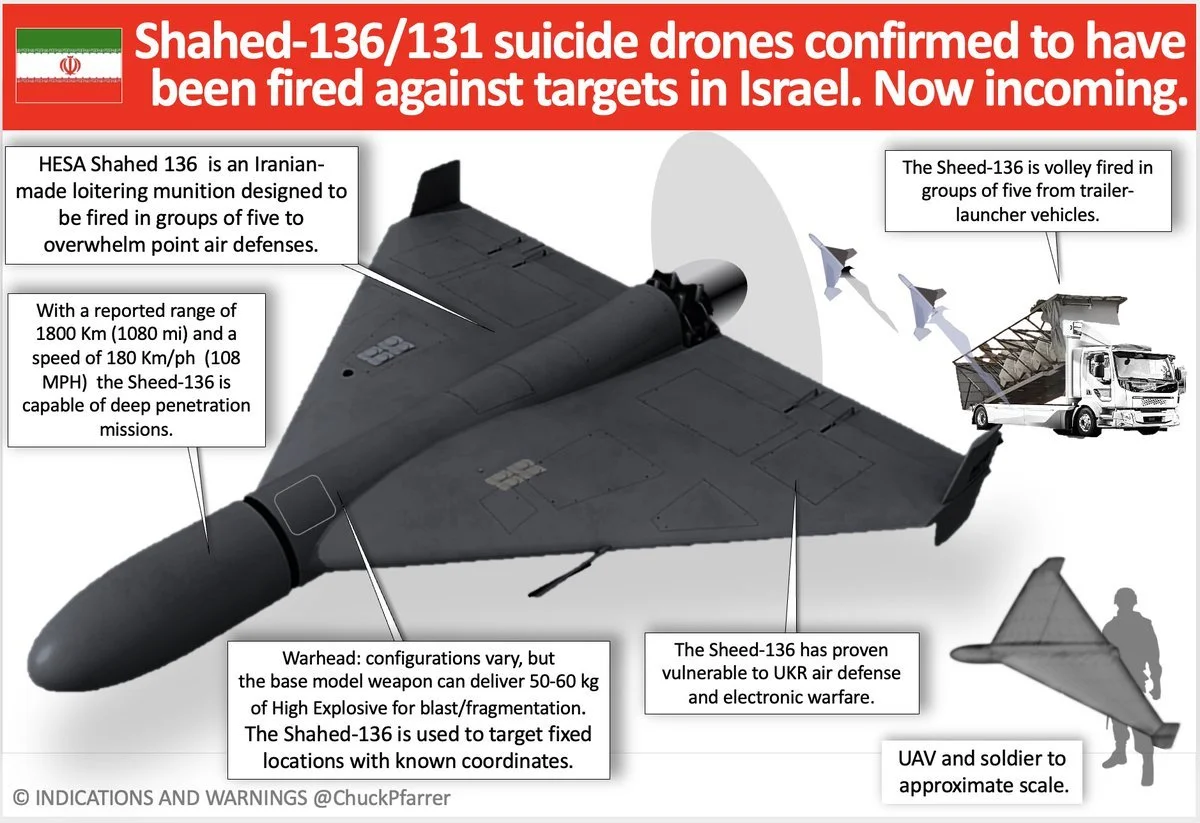

These Shaheds were built from the start as loitering munitions, drones with explosive warheads and no intention of returning to provide critical information. The Shahed-131 carries a warhead of roughly 15 kg and has a range of around 900 km. It contains a Wankel-type rotary engine. This simplistic design is reliable for its intended suicide mission. The larger version, the Shahed-136, is vastly different, with a delta wing, pusher-prop design, and a significantly heavier 200 kg weight. Open-source estimates suggest that this drone has a speed of 185 km/h and potentially a range in the thousands of kilometers. These Shahed drones are cheap, costing an estimated tens of thousands of dollars. This low cost supports the idea that these drones can be fired in large groups, intended to overwhelm enemy forces, and high attrition rates are seen as acceptable.

The biggest turning point for this drone was in 2022, when Ukrainian forces reported delta-shaped drones used by Russian forces landing in Ukrainian settlements. The rebranding of the Shahed became known as the Geran-1 and Geran-2. These drones were specifically designed to target urban populations. Their effectiveness derives from saturation, psychological impact, and cost. If one Geran is able to surpass air defenses, its impact could potentially cause hundreds or thousands of civilian casualties. It could also cripple supply lines and force adversaries to expend their munitions to stop a single drone.

There are several reasons why the Shahed-series drone is a massive success for Iran and its allies. Compared to conventional missiles or bombs, a single Shahed can cost a fraction of what a missile costs. Losses can be tolerable and may encourage large-volume launches. The Shahed’s simple airframe and dual‑use of commercially available parts makes mass production easier. For a nation’s drone program born under sanctions, this makes it easier for countries that are heavily sanctioned by the international community to bypass restrictions. Drone swarms can force defenders to expend munitions and strain air defense planning, which in turn drains resources. These Shahed drones do not require runways and can be launched off trucks. This allows drone operators the flexibility to deploy Shaheds from almost any location.

However, it is not without limitations. These basic drones do not have any known stealth technology. Due to the fact they are mass-produced, there are no advanced targeting capabilities or cloaking countermeasures. This makes them vulnerable to detection, electronic warfare, or air defense. While these drones are expendable, many Shaheds are shot down in significant quantities. A single Shahed drone is not a major threat in and of itself; it relies on multiple Shaheds. As air defenses improve, with better jamming capabilities and multiple interception methods, the return on investment decreases. These drones are not a substitute for missiles, but they are a cheap alternative meant to demoralize adversary forces.

The story of the Shahed drone series is important because it illustrates a fundamental shift in modern warfare: the ability of small, resource-constrained nations to leverage technology and ingenuity to project power asymmetrically. Through cost-effective design, mass production, and a philosophy of expendability, Iran has transformed what was once a reconnaissance tool into a strategic weapon capable of influencing conflicts far beyond its borders. The Shahed program highlights how drones can redefine deterrence, challenge conventional air defenses, and impose psychological and material costs on opponents at minimal expense. More broadly, it signals that future conflicts will increasingly revolve around innovation, swarm tactics, and the use of low-cost unmanned systems to achieve outsized effects, making the Shahed not just a weapon, but a lens through which to understand the evolving nature of twenty-first-century warfare.