Mohajer Drone: Crude Creation to Cutting-Edge

During the Iran–Iraq War, Iran faced a crisis that threatened its survival as a new nation. The country’s air force was built on Western supply chains, and crippling sanctions, combined with a conventional war, quickly strained its operational capabilities. Western-led sanctions imposed after the 1979 Revolution began to take a toll on Iran’s ability to deploy and maintain aircraft. Cut off from the means to repair and produce manned aircraft, as well as from advanced sensors and reconnaissance technology, Iran began to explore unmanned options.

A small team from the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps produced crude unmanned aircraft. While improvised and limited, these early drones paved the way for Iran to become a formidable drone power in the Middle East. Its first operational drone, the Mohajer, was born out of necessity, yet this simple aircraft sparked a systematic transformation in Iran’s military-industrial capabilities. The Mohajer became the cornerstone of Iranian UAV doctrine: low-cost, locally produced, exportable, and resilient.

This article examines Mohajer’s evolution from a crude drone built under duress to a mature platform that now threatens American interests in the region and explains how it helped establish Iran as a formidable adversary in modern aerial warfare.

When the Islamic Republic of Iran was established in 1979, the new government quickly demonstrated hostility toward Western powers, most notably through the seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. In response, the United States imposed a swift and comprehensive package of sanctions aimed at crippling Iran’s financial, military, and industrial sectors. These measures froze Iranian assets and severely restricted the conventional expansion of its military. Other nations soon followed suit, sanctioning the newly founded Islamic Republic and targeting industries vital to the procurement of aircraft and related technologies.

The sanctions were designed to ensure that Iran would not emerge as a military threat in the Middle East. Iranian industry relied heavily on imported machinery, components, and technology, and restricting access to these materials made acquiring aircraft, sensors, and avionics extremely difficult. Iran was effectively cut off from upgrading its arsenal or expanding its capabilities.

When Iraq invaded in 1980, these pressures intensified. Fighting a conventional war under the weight of sanctions made deploying manned aircraft into enemy territory both dangerous and strategically costly. Conventional airpower, essential for reconnaissance, close air support, and deploying forces into hostile territory, was no longer a feasible option. Iranian military strategists were forced to innovate.

This combination of sanctions and wartime necessity gave birth to the Mohajer program. A team of Iranian scientists began developing inexpensive unmanned aerial vehicles, producing the Mohajer-1 in 1985. Manned aircraft were costly to replace, but these drones allowed Iranian forces to conduct reconnaissance over Iraqi positions without risking pilots or further straining the country’s depleted economy. Ironically, the very sanctions intended to cripple Iran’s military capabilities indirectly fostered the development of its domestic drone program, laying the foundation for a UAV doctrine that persists to this day.

The Mohajer 1 was developed because Iran was struggling on the battlefield due to a lack of actionable intelligence. Constraints imposed by Western sanctions forced Iranian engineers to work with limited materials and minimal guidance. The drone featured a narrow cylindrical fuselage with straight wings, designed for stability rather than aerodynamic efficiency. Its components were made from locally sourced materials, including aluminum tubing, and its propulsion system was a small piston engine, loud and limited in range, but sufficient to carry the Mohajer 1 over short distances.

Its basic control systems were severely limited. Operators relied on line-of-sight radio links, and drones were deployed from forward operating bases near the front lines. There were no autopilot capabilities or over-the-horizon control, leaving operators exposed to counterattack and making the drone highly vulnerable to interference. Flight performance depended heavily on operator skill and the reliability of the mechanical components. Since construction was not uniform, individual Mohajer 1s could vary in materials and quality. The drone could not transmit images in real time; it could only photograph targets directly below it. To gather intelligence, it had to fly specific patterns over enemy positions and be safely recovered by Iranian teams, a risky process behind enemy lines.

The Mohajer 1 carried a simple film camera, and its intelligence was limited and delayed. By the time the film was developed, Iraqi forces could have moved positions. Nevertheless, the intelligence gathered was sufficient to provide tactical advantages. In experimental stages, Iran attempted to arm the Mohajer 1 with small rockets, but these efforts were unsuccessful. Even in its basic form, the drone allowed Iranian forces to map enemy positions and gather reconnaissance without risking pilots or costly manned aircraft.

Early missions often failed. The crude piston engine could stall, communication with operators was lost, and crashes sometimes destroyed the onboard camera. Each failure, however, provided valuable lessons. Recovered drones revealed which components survived crashes, allowing operators to salvage durable parts and replace fragile ones. While the Mohajer 1 was soon replaced by improved variants, it laid the foundation for Iran’s drone program and strategy in unmanned warfare. Its legacy was so impactful that an Iranian film, The Immigrant (Mohajer), was produced to showcase its deployment on the battlefield.

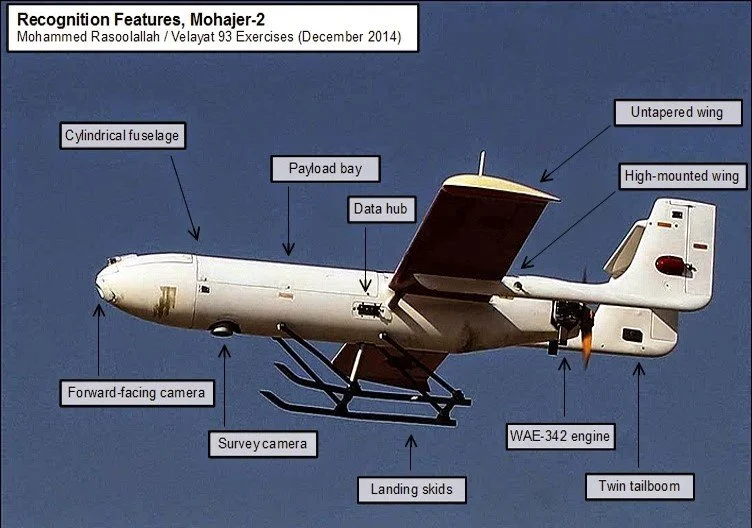

Building on the lessons of the first drone, Iran’s UAV program rapidly evolved. The next generation, the Mohajer 2, addressed many of the limitations of its predecessor. The Mohajer 2 featured significantly improved flight stability, a larger airframe, and greater endurance. Iranian engineers incorporated more reliable engines and refined control surfaces, enhancing maneuverability and extending operational range. The drone also carried upgraded reconnaissance capabilities, accommodating larger cameras and improved film systems, which allowed for more detailed and actionable imagery. This enhanced intelligence enabled Iranian forces to better coordinate large-scale operations and make more informed tactical decisions. The Mohajer 2 could operate for longer durations and had improved recovery systems, increasing its reliability and longevity on the battlefield.

The subsequent evolution, the Mohajer 3, featured a significantly larger airframe, greater endurance, and a stronger propulsion system. These improvements allowed the drone to operate in more contested environments and cover longer distances, effectively keeping operators out of harm’s way. The Mohajer 3 retained the high-wing design of earlier models but incorporated structural reinforcements and more advanced avionics, reflecting the engineers’ growing ability to innovate under sanctions. While the Mohajer 3 could successfully integrate light munitions, these were initially limited to test deployments, marking the beginning of Iran’s exploration into armed UAV capabilities.

By the time the Mohajer 3 was mass-produced, Iran had established a fully functional system for designing, launching, controlling, recovering, and analyzing drone missions. This operational framework was a significant advantage on the battlefield, transforming experimental drones into a core component of Iranian military strategy. Both the Mohajer 2 and Mohajer 3 also allowed Iran to extend its influence beyond its borders. These low-cost UAVs were supplied to proxy forces and allied states, demonstrating the strategic value of domestically produced unmanned aerial technology. The program established a foundation for iterative improvements, operational standardization, and regional power projection, setting the stage for more advanced and versatile UAVs in the decades that followed.

The Iranian drone program had a profound impact. What began as a solution to an operational problem became the blueprint for a domestic UAV industry and an enduring military doctrine. Iran demonstrated that even under isolation from the international community, it could pose a credible military threat. Ironically, the very sanctions intended to cripple its military capability inadvertently strengthened it by forcing the development of drones. Drone warfare allows military forces to overcome operational disadvantages at a fraction of the cost, and Western sanctions effectively created an Iranian UAV industry that remains influential to this day.

One of the key doctrinal lessons learned was the value of low-cost, expendable systems. By prioritizing simplicity, domestic production, and operational resilience, Iran developed UAVs that provided significant strategic advantages. Each iteration of the Mohajer program reinforced these design principles and demonstrated an important aspect of drone warfare: failures were as instructive as successes. When a drone successfully gathered intelligence, it enhanced the Iranian military’s operational picture. When a drone failed, the IRGC could study the cause, apply the lessons learned, and improve subsequent designs. Over time, this iterative process made Iranian UAVs increasingly reliable and effective. Drones became force multipliers that could bypass traditional air defenses, exert intelligence pressure on adversaries, and provide Iran with asymmetric advantages in regional conflicts.

The Mohajer program illustrates how necessity and constraint can drive innovation. What began as a crude solution to battlefield intelligence gaps evolved into a sophisticated domestic UAV industry, reshaping Iran’s military capabilities and strategic posture. From the Mohajer 1 to the Mohajer 3, each iteration refined both technology and doctrine, demonstrating the value of iterative learning, low-cost systems, and operational resilience. Today, Iran’s UAV program stands as a testament to strategic ingenuity under pressure, providing lessons in adaptability, asymmetric warfare, and the enduring impact of innovation born from necessity.